Helmholtz decomposition

In physics and mathematics, in the area of vector calculus, Helmholtz's theorem, also known as the fundamental theorem of vector calculus, states that any sufficiently smooth, rapidly decaying vector field in three dimensions can be resolved into the sum of an irrotational (curl-free) vector field and a solenoidal (divergence-free) vector field; this is known as the Helmholtz decomposition. It is named after Hermann von Helmholtz.

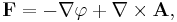

This implies that any such vector field F can be considered to be generated by a pair of potentials: a scalar potential φ and a vector potential A.

Contents |

Statement of the theorem

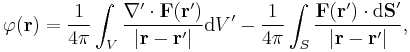

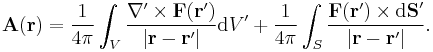

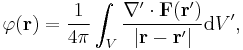

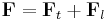

Let F be a vector field on a bounded domain V in R3, which is twice continuously differentiable. Then F can be decomposed into a curl-free component and a divergence-free component[1]:

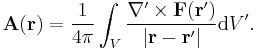

where

If V is R3 itself (unbounded), and F vanishes sufficiently fast at infinity, then the second component of both scalar and vector potential are zero. That is,[2]

Fields with prescribed divergence and curl

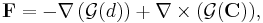

The term "Helmholtz Theorem" can also refer to the following. Let C be a solenoidal vector field and d a scalar field on R3 which are sufficiently smooth and which vanish faster than 1/r2 at infinity. Then there exists a vector field F such that

and

and

if additionally the vector field F vanishes as r → ∞, then F is unique.[2]

In other words, a vector field can be constructed with both a specified divergence and a specified curl, and if it also vanishes at infinity, it is uniquely specified by its divergence and curl. This theorem is of great importance in electrostatics, since Maxwell's equations for the electric and magnetic fields in the static case are of exactly this type.[2] The proof is by a construction generalizing the one given above: we set

where  represents the Newtonian potential operator. (When acting on a vector field, such as ∇ × F, it is defined to act on each component.)

represents the Newtonian potential operator. (When acting on a vector field, such as ∇ × F, it is defined to act on each component.)

Differential forms

The Hodge decomposition is closely related to the Helmholtz decomposition, generalizing from vector fields on R3 to differential forms on a Riemannian manifold M. Most formulations of the Hodge decomposition require M to be compact.[3] Since this is not true of R3, the Hodge decomposition theorem is not strictly a generalization of the Helmholtz theorem. However, the compactness restriction in the usual formulation of the Hodge decomposition can be replaced by suitable decay assumptions at infinity on the differential forms involved, giving a proper generalization of the Helmholtz theorem.

Weak formulation

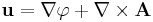

The Helmholtz decomposition can also be generalized by reducing the regularity assumptions (the need for the existence of strong derivatives). Suppose Ω is a bounded, simply-connected, Lipschitz domain. Every square-integrable vector field u ∈ (L2(Ω))3 has an orthogonal decomposition:

where φ is in the Sobolev space H1(Ω) of square-integrable functions on Ω whose partial derivatives defined in the distribution sense are square integrable, and A ∈ H(curl,Ω), the Sobolev space of vector fields consisting of square integrable vector fields with square integrable curl.

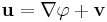

For a slightly smoother vector field u ∈ H(curl,Ω), a similar decomposition holds:

where φ ∈ H1(Ω) and v ∈ (H1(Ω))d.

Longitudinal and transverse fields

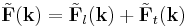

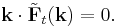

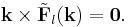

A terminology often used in physics refers to the curl-free component of a vector field as the longitudinal component and the divergence-free component as the transverse component.[4] This terminology comes from the following construction: Compute the three-dimensional Fourier transform of the vector field F, which we call  . Then decompose this field, at each point k, into two components, one of which points longitudinally, i.e. parallel to k, the other of which points in the transverse direction, i.e. perpendicular to k. So far, we have

. Then decompose this field, at each point k, into two components, one of which points longitudinally, i.e. parallel to k, the other of which points in the transverse direction, i.e. perpendicular to k. So far, we have

Now we apply an inverse Fourier transform to each of these components. Using properties of Fourier transforms, we derive:

so this is indeed the Helmholtz decomposition.[5]

Notes

- ^ "Helmholtz' Theorem". University of Vermont. http://www.cems.uvm.edu/~oughstun/LectureNotes141/Topic_03_(Helmholtz'%20Theorem).pdf.

- ^ a b c David J. Griffiths, Introduction to Electrodynamics, Prentice-Hall, 1989, p. 56.

- ^ Cantarella, Jason; DeTurck, Dennis; Gluck, Herman (2002). "Vector Calculus and the Topology of Domains in 3-Space". The American Mathematical Monthly 109 (5): 409–442. JSTOR 2695643.

- ^ [0801.0335] Longitudinal and transverse components of a vector field

- ^ Online lecture notes by Robert Littlejohn

See also

- Darwin Lagrangian for an application

References

General references

- George B. Arfken and Hans J. Weber, Mathematical Methods for Physicists, 4th edition, Academic Press: San Diego (1995) pp. 92–93

- George B. Arfken and Hans J. Weber, Mathematical Methods for Physicists International Edition, 6th edition, Academic Press: San Diego (2005) pp. 95–101

References for the weak formulation

- C. Amrouche, C. Bernardi, M. Dauge, and V. Girault. "Vector potentials in three dimensional non-smooth domains." Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences, 21, 823–864, 1998.

- R. Dautray and J.-L. Lions. Spectral Theory and Applications, volume 3 of Mathematical Analysis and Numerical Methods for Science and Technology. Springer-Verlag, 1990.

- V. Girault and P.A. Raviart. Finite Element Methods for Navier–Stokes Equations: Theory and Algorithms. Springer Series in Computational Mathematics. Springer-Verlag, 1986.

|

|||||||||||